Why the Mafia Fell — and Who Took Its Place

The Rise Before the Fall

There was a time when the Mafia didn’t just run neighborhoods — it ran cities. From New York to Chicago, from the docks to the casinos, organized crime was a parallel government. It had its own laws, its own enforcement, and its own code. And if you crossed it, you didn’t get a warning — you got buried.

But the Mafia didn’t start as the monster it became. It rose from necessity — from poverty, discrimination, and survival. Italian immigrants arriving in America in the late 1800s were treated like animals. Denied jobs, mocked, shut out of society, and crammed into slums. The American dream didn’t greet them — it spit on them.

So they built their own system.

It started small. Protection rackets. Street-level enforcement. Unions. Gambling. Black hand extortion. Then came Prohibition in the 1920s — and everything changed. The government outlawed alcohol, but the people still wanted it. That created a perfect storm: massive demand, illegal supply, and the Mafia ready to deliver. Bootlegging made mobsters rich overnight. It also made them powerful.

Guys like Al Capone weren’t just criminals — they were celebrities. He fed the poor and gunned down rivals. He was both feared and admired. And he wasn’t alone. Luciano, Lansky, Siegel, Nitti — they weren’t just mobsters. They were kings without thrones, CEOs without titles. By the 1930s and 40s, the Mafia was a shadow state.

What made it work wasn’t just violence. It was structure. Honor. Rules. You couldn’t just walk in and become a made man. You had to be vouched for. You had to prove loyalty. You had to bleed for the family. The Mafia was built on omertà — the code of silence. Breaking it was death.

And for decades, that code held.

They infiltrated unions. Owned construction companies. Fixed boxing matches. Bribed judges. Paid off cops. Controlled the ports. Rigged bids. Ran loan shark operations, numbers games, and illegal casinos. In some cities, the mob made more than the government.

But power breeds arrogance. And arrogance breeds vulnerability.

By the 1950s and 60s, the Mafia had reached its golden age — but it also started making enemies. The FBI, which had long denied the existence of organized crime, couldn’t look away anymore. The famous 1957 Apalachin meeting, where dozens of mob bosses were arrested in upstate New York, blew the doors off the secret world. The government could no longer pretend the Mafia was just a myth.

Still, the Mafia kept growing. Guys like Carlo Gambino, Vito Genovese, and Joseph Colombo ran multibillion-dollar operations without lifting a finger. Murder Inc. enforced rules with ice picks and bullets. The Five Families of New York — Gambino, Genovese, Lucchese, Colombo, and Bonanno — operated like corporations. They had sit-downs instead of board meetings. Crews instead of departments. But the structure was just as strong.

And for a long time, it worked.

Why? Because people preferred it. In neighborhoods where the mob operated, things were… safe. You didn’t rob a corner store protected by the Mafia. You didn’t touch a woman who belonged to a wiseguy. You didn’t sell drugs on their turf — not without permission. There was a twisted sense of justice. Of order.

Even law-abiding citizens knew who really ran the block. If your kid got jumped, the mob would take care of it faster than the cops. If someone tried to scam your grandmother, they’d disappear. To many people, the mob wasn’t the enemy. It was the unofficial government — and it worked better than the real one.

But all empires rot from within.

The seeds of the Mafia’s downfall weren’t planted by the government. They were planted by the mob itself — in the form of greed, betrayal, and ego. The rules that once held it all together started to bend. Then they broke. Guys started talking. Started flipping. Started choosing survival over silence.

And when that happened — the fall wasn’t just inevitable. It was explosive.

The golden age of the Mafia was over. The storm was coming. And what came next would shatter everything.

RICO, Rats & Ruin

The fall of the American Mafia didn’t happen overnight. It came like a slow collapse, with cracks spreading from within — but when it broke, it broke hard. And the main weapon that brought it down wasn’t a gun. It was a law: RICO.

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, passed in 1970, changed the game. Before RICO, law enforcement could only go after individual crimes — murder, extortion, loan sharking. But mob bosses rarely touched anything themselves. They gave orders, moved through layers, kept their hands clean. RICO changed that. Now the feds could charge an entire organization and take down bosses for crimes committed by their soldiers.

It was designed to dismantle criminal empires. And that’s exactly what it did.

In the 1980s and 90s, the FBI, NYPD, and federal prosecutors declared war. Wiretaps, undercover agents, flipped informants — the Mafia was suddenly under a microscope. Guys who once strutted down Mulberry Street were now speaking into hidden wires. Sit-downs became surveillance opportunities. Taps were placed in social clubs, cars, even in homes. Nothing was safe.

But it wasn’t just technology that brought the Mafia down. It was loyalty — or the lack of it.

The code of silence — omertà — began to crack. Facing 30 years to life, guys started flipping like dominoes. Made men. Captains. Even underbosses. No one was off-limits. When Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, underboss of the Gambino family, flipped in 1991 and testified against John Gotti, it sent shockwaves through the entire underworld. Gotti, the flashy “Dapper Don,” once untouchable, went down like a common thug.

Sammy the Bull’s testimony led to the conviction of over 30 mobsters — and it set a precedent. After him, more followed. Joe Massino, boss of the Bonanno family. Phil Leonetti, underboss of the Philly mob. Tommy “Karate” Pitera’s guys. The Mafia was now being eaten from the inside.

Each trial pulled the curtain back. Jurors, the public, and the media saw the Mafia not as men of honor, but as backstabbing, greedy criminals. The mystique was dying. The fear was fading.

And with each conviction, the structure collapsed.

RICO didn’t just send men to prison. It seized their homes, froze their bank accounts, took their unions, and crippled their cash flow. Being in the mob was no longer a golden ticket — it was a prison sentence waiting to happen.

Law enforcement also started targeting the old strongholds. The Mafia used to own the garbage industry, the ports, construction bids. But now feds were planting undercover agents in unions. Legit businesses stopped paying protection. Contractors no longer feared the mob. Why? Because the threat of getting whacked was replaced by the reality of getting wiretapped.

Technology changed everything. Phone taps. Hidden mics. Surveillance vans. GPS trackers. Things that didn’t exist in the 50s were now closing in. Mobsters could no longer meet at diners or social clubs without being watched. The mob’s biggest strength — secrecy — became its biggest weakness.

And then came the culture shift.

New generations of Italian-Americans didn’t want the life. They wanted college, clean money, peace. They didn’t want to risk 25 years for some street corner their uncle died protecting. The glamor was gone. The loyalty was gone. The code was gone.

Even inside the Mafia, the rules broke down. No drugs used to be the standard. But drugs made money — lots of it. So guys sold heroin and cocaine behind closed doors. When they got caught, they flipped. Greed beat tradition.

And as bosses got taken down, what rose in their place wasn’t order — it was chaos. Rats everywhere. Informants in every crew. Social clubs closed. Shakedowns stopped. And the public? They didn’t fear the mob anymore. They watched them on TV.

Shows like The Sopranos and movies like Goodfellas turned the Mafia into entertainment. The real-life consequences were replaced with dramatized nostalgia. But the streets told a different story: the mob was bleeding out.

By the 2000s, the Mafia wasn’t dead — but it was a ghost of what it was. Crews still existed. Guys still got made. But the fear was gone. The dominance was gone. The loyalty was buried under plea deals.

And in the void left behind, a new kind of power stepped in. Not as romantic. Not as flashy. But just as dangerous.

The era of the traditional American Mafia was ending.

And something far bigger — and less predictable — was taking its place.

The New Kings: Cartels, Gangs & Corporations

The Mafia fell, but organized power didn’t disappear — it evolved. The collapse of traditional Cosa Nostra left behind a vacuum, and in the real world, power vacuums don’t stay empty. They get filled fast. What replaced the Mafia wasn’t one enemy — it was a hydra with many heads. Cartels. Street gangs. Cybercriminals. Tech monopolies. Government-backed syndicates. The tools changed, the names changed, but the motive stayed the same: control.

Let’s start with the most obvious replacement — the cartels.

While the American Mafia collapsed under indictments and betrayals, Mexican and South American drug cartels exploded in size and reach. Groups like Sinaloa, Jalisco New Generation, and Los Zetas became multinational corporations of terror. They didn’t operate in the shadows — they controlled cities. They bought politicians, slaughtered enemies, and moved billions in product across borders. And unlike the Mafia, they didn’t care about “rules.”

Cartels didn’t hesitate to butcher civilians. Kidnap journalists. Blow up police stations. Where the Mafia used a knife in the dark, the cartels used AK-47s in broad daylight. They weren’t just more violent — they were more global. Cocaine, heroin, meth — they didn’t just distribute, they owned the entire pipeline: from jungle labs to urban street corners.

And they used the very tools the Mafia never mastered — technology, smuggling networks, encrypted communication, and international finance.

Then came the street gangs. MS-13. Bloods. Crips. Latin Kings. Their rise paralleled the Mafia’s fall. Where the mob had structure and hierarchy, gangs had numbers, reach, and youth. They flooded American cities with drugs and violence. Their recruitment wasn’t selective — it was aggressive. Kids as young as 12 carried guns. Loyalty was enforced through fear and initiation.

In many inner-city neighborhoods, gangs replaced what the Mafia once was: the unofficial power. They handled protection. They resolved disputes. They enforced street law. And they did it without suits, without sit-downs — just blood.

But not every new power looked like a criminal.

Some wore suits. Carried laptops. Sat in glass towers. That’s where corporations come in.

After the Mafia’s fall, a new breed of organization quietly took over the control once held by crime families — only legally. Big Tech, Big Pharma, Big Banks — they didn't break legs, but they broke minds, broke economies, and broke entire generations.

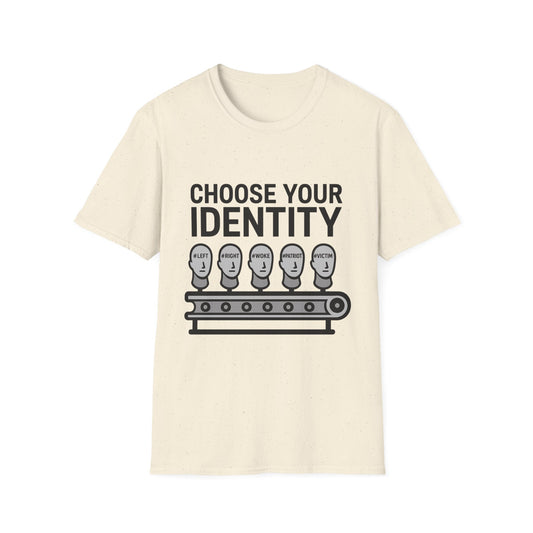

Tech monopolies learned how to do what the mob never could: addict the population willingly. Social media replaced slot machines. Data replaced debt. Screen time replaced street time. And instead of protection rackets, people paid willingly with their time, attention, and privacy.

Who controls more minds today — a mob boss in 1980 or a tech CEO in 2024?

The answer isn’t even close.

And then there’s the government itself — often indistinguishable from organized power. Surveillance programs. Secret deals. Proxy wars. You think the mob was corrupt? Try tracking how billions in tax dollars disappear into “classified” budgets, black ops, and corporate bailouts. It’s not that organized crime went away — it got absorbed into the system.

They don’t need Tommy Guns anymore. They have contracts. Laws. Algorithms.

We traded the Godfather for Google. The capo for the coder. The street soldier for the screen addict. And yet the outcome is eerily similar: obedience. Dependency. Control.

You don’t need fear when you have convenience.

And that’s why the fall of the Mafia didn’t end organized power — it evolved it. The mob ruled by bullets and honor. The new kings rule by data, dollars, and dopamine. And they don’t hide it. They put it in your pocket, on your feed, in your bloodstream.

So who replaced the Mafia?

Everyone who understood that control is more effective when it doesn’t look like control at all.

Why the Mob Still Matters Today

Most people think the Mafia died when the headlines stopped. When Gotti went away. When the social clubs closed. When the FBI said “mission accomplished.” But they’re wrong. The Mafia never disappeared — it just became part of the culture. And even if it vanished tomorrow, the impact it had on America would still be pulsing through the bloodstream of the country.

Why? Because the Mafia wasn’t just crime. It was identity. It was structure. It was a philosophy, however flawed — built on loyalty, power, family, and fear.

In a world where everything feels disposable — the mob was one of the last systems where your word mattered. Where betrayal cost more than just a few followers or a slap on the wrist. It cost your life. That weight gave things meaning.

Even in its darkest moments, the Mafia had something the modern world lacks: accountability.

You didn’t get to lie, cheat, steal, or backstab without consequence. You didn’t get to disrespect someone and walk away untouched. There were rules. Codes. Standards. Twisted? Maybe. But effective? Undeniably. Compare that to today’s society — where trolls hide behind screens, influencers sell their souls for clout, and corporate snakes smile while stabbing you.

People romanticize the mob because, deep down, we all know: at least it stood for something.

It also reflected something deeper — a hunger for power in the hands of people instead of institutions. When the government failed you, the mob stepped in. When the cops didn’t come, the neighborhood knew who to call. The Mafia filled the gaps that society ignored. That’s not a justification. That’s a reality.

Today, those gaps still exist. But instead of being filled by neighborhood tough guys who grew up on the block, they’re filled by automated systems, soulless bureaucracies, and cold algorithms.

And even though the Mafia no longer holds real power, its mythos still does.

Mob movies are more popular than ever. Sopranos clips flood social media. TikToks explain what “omertà” means. Teenagers quote Michael Corleone like scripture. Why? Because the Mafia was real. Because it was raw. Because it showed a version of life where men had to stand for something — or die for nothing.

The mob gave men a model — even if a broken one — of how to move, how to command respect, how to handle betrayal, and how to lead. That doesn’t make it noble. But it does make it memorable. And right now, in a world where everyone’s pretending, people crave something real — even if it’s from the underworld.

The Mafia’s legacy isn’t about organized crime. It’s about the void it leaves behind — a void of respect, order, and human connection. It’s about a time when people actually knew who ran the block. When loyalty meant something. When you could call someone “boss” and mean it.

That’s why the mob still matters today.

Not because we need more gangsters.

But because we need more backbone.